Caring for Country and Ourselves: Bushfires and what the "new normal" means for our food system

Kelly Donati, Chair, Sustain

The catastrophic and unprecedented bushfires represent a food crisis, not just for humans but for all the lives with whom we share this continent.

Fire and water, too much of one and not enough of the other, have dominated the news cycle in Australia for many months. 2019 began dramatically with reports of the first wave of fish kills in the Darling River. Macabre images of rotting, bloated carcasses of dead Murray Cod flooded the news and social media feeds.

Facebook: Debbie Newitt via ABC

When the story broke, I was driving back from the pristine Wallagaraugh River in the farthest reaches of East Gippsland. The accounts that emerged of a dying river felt all the more stark against the contrast of the Wallagaraugh’s gentle flow. The sound of mullet dancing across the water’s shimmering surface lulled me to sleep at night and delighted me as I meandered down the river in a tinny while the afternoon sun dipped behind the eucalypts.

As we entered the new decade, flames engulfed those trees as though they were mere kindling. That’s what much of the landscape has become: fuel for the catastrophic fires the best experts had warned were coming. When rain finally comes, ash will pollute what remains of our waterways.

The apocalyptic images of thousands of locals and tourists trapped on the beaches of Mallacoota, the sky painted blood-red and then pitch black remind us of the terrifying force of these firestorms.

Twitter: @Brendanh_au

Nor were New South Wales and even Queensland rainforests spared from the fury. Firefighters and local residents have perished protecting towns and properties. Thousands are without homes.

Many Aboriginal communities have been similarly devastated. Beyond the loss of homes, fire has ripped through sacred sites; the Mogo Local Aboriginal Land Council office has burnt to the ground, and along with it, critical documentation for the Monaro and Yuin communities.

Cities are bathed in hazardous smoke that is settling on glaciers in New Zealand. This ecological crisis will quickly manifest into a public health crisis.

Instagram: @geoffp63

Now’s not the time to speak about climate change, we are told.

This nightmare has been building over several months. Heat waves are no longer singular events. They are now waves of record-breaking waves, each sucking more moisture from a parched landscape. Today the southern reaches of the Darling River are little more than a trickle. The river can no longer sustain life. Communities along its banks no longer have water.

Desperate farmers, barely hanging on, now face even greater challenges. Throughout 2019, we witnessed heartbreaking images as many struggled to feed their animals who stand listlessly in dusty paddocks. Some are selling up. Others speak of the relentless mental grind of waiting for rain, living in hope while topsoil blows away. Scorched pasture means dairy cattle have no food, and lack of power has meant fresh milk—and the precious water embedded in it—is being poured down the drain. City dwellers are exhorted to buy locally and support fire-affected regions. And so we must.

The bushfires have revealed the best of what communities can do. Exhausted firefighters pushed to physical and emotional limits have saved human lives and properties. Humans have reached out to help animals; animals have reached out to humans in the most remarkable ways. People have worked together, supported each other and will somehow struggle through.

Instagram: @bikebug2019

But none of this is enough.

We are witnessing the great unravelling of a food system that is much bigger than us. Fires of this scale destroy the precious layer of humus that holds the water, decomposed organic matter and microbial life that nourishes forests and other vegetation. The canopies of eucalypt forests have been rendered ash on forest floors. Koala communities, already fragile, have been decimated; those that remain are starving without leaves to feed them. Singed but surviving wallabies, possums and kangaroos search for food across a blackened landscape.

Twitter: @ShelCalopa

Insect communities have experienced an annihilation that will leave birds, and others who depend on them, hungry. The charred bodies of livestock, caught by fences, on the side of the road, have traumatised farmers, firefighters, animal rescuers, journalists and local residents either evacuating or returning home. Over a billion animals—and entire species—have been lost.

Now is the time for us to take seriously how deeply interconnected all life is. Policy responses to global climate change and to its local effects will need to be multi-pronged, accounting for the global issue of carbon emissions but also attending to how we will care for other species with whom we share this land.

Centuries of colonialism have revealed just how ill-equipped settler-colonial Australia is to care for stolen lands. It is time to acknowledge that eating and living well in this country, on and from Country, depends on the knowledge of its original inhabitants, those whose deep understanding of fire has cared for it over tens of millennia. To ignore this is to imperil all life in this country, particularly as recent reports suggest some remote Aboriginal communities are situated in places that may be too hot to inhabit in coming years. As though violent dispossession and genocide were not enough, people living in these communities risk becoming climate refugees in their own country. This should make us deeply ashamed.

The late environmental philosopher Deborah Bird Rose described the Aboriginal concept of Country as a ‘nourishing terrain, a place that gives and receives life.’ As communities gather themselves up from the ashes, we must remember this most powerful concept—a place that gives and receives life. For our inaction, and our casual disregard, threatens the reciprocity and fabric of life at its core.

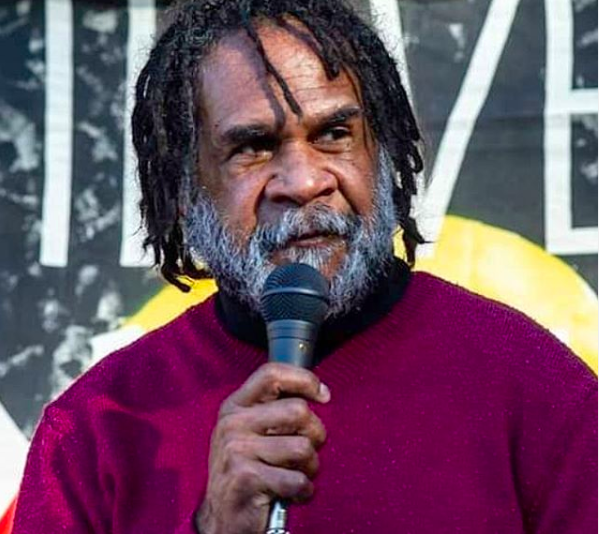

Late last year Bruce Shillingsworth, a Muruwari and Budjiti artist and river activist from the north-west riverlands of NSW, appeared on ABC’s Qanda with a simple but powerful warning: ‘Australia needs to wake up!’ He angrily lamented how a river system that fed people for millennia has died in the pursuit of profits over life, comprising the health of its people and the other beings that rely on it—a second wave of genocide. His message is a reminder of what is at stake as we collectively make sense of these fires mean for the future: irreparable damage to an ancient food system that has sustained all forms of life—human, nonhuman and ancestral—through the most intimate ecologies of care.

Instagram: @bruceshillingsworth

The time for incremental change has long passed. We need to demand that Aboriginal communities have access to land and are adequately resourced to practice the cultural burning on which this land depends. Regional communities need more regenerative farmers who care for the soil’s underground networks of plants, fungi and microbes. We need environmental policies that integrate the landscapes that feed humans and nonhumans alike. We must end the farce that human food systems are separate from the food systems that nourish other creatures in forests, waterways, coastlines and grasslands.There is only one food system, and that is the planet on which we live.

Dr Kelly Donati is the founding Chair of Sustain: the Australian Food Network, a Lecturer in food studies and gastronomy at William Angliss Institute and a 2019/2020 research fellow at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society.

Sustain wishes to extend our deepest sympathies and support for those communities affected by fire and encourage donations to the following organisations:

Fire Relief Funds for First Nations Communities