With Love, From Lily

Kelly Donati, Co-Chair, Sustain / Lecturer, William Angliss Institute

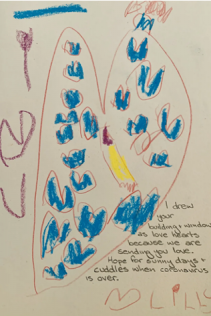

Lily, aged 5, had a message for the residents of public housing estates placed under hard lockdown in Melbourne on 7 July. In her drawing submitted to The Age, a tower block and its windows were represented in the form of love hearts because, she explains, ‘we are sending you love. Hope for sunny days and cuddles when coronavirus is over.’

I’m in no position to dispute public health experts about the need for a hard lockdown on the towers, and I don’t deny these are difficult times calling for difficult decisions. But there are better and worse ways of doing things. As a result of a sustained and strong police presence, many residents of the tower block communities reported feeling targeted, vilified and blamed for the concerning rise in Covid-19 cases. A single mother with multiple children described going without sufficient quantities of food to feed her children. Others expressed surprised at seeing prison-quality food dropped off at their doorstep in the middle of the night. The ratio of police to social workers and health professionals felt disproportionate for what was public health crisis—not a matter of law and order.

I wonder what scenes at the North Melbourne and Flemington tower blocks would have looked like if Lily was coordinating the response because, at the risk of sounding romantic, this situation called for less force and more love. A loving response would have put the needs of the residents first.

A loving response would have started with immediate and direct consultation and communication with those community organisations that had the confidence of the residents. Food would have been of the utmost priority rather than the afterthought that it appeared to be.

Many amazing food relief organisations mobilised themselves with lightning speed, understanding the criticality of food to people’s wellbeing. Yet there have been reports of multiple roadblocks in getting fresh, culturally-appropriate food to residents’ apartments. At best, the food situation was unevenly organised. At worst, it was shambolic.

Wondering about their next meal, residents watched from their windows as police swarmed around their buildings. Their neighbours, under a very different form of lockdown, went freely about their business: walking their dogs, doing groceries and enjoying a spot of exercise in the fresh air. Imagining myself at one of those windows, I feel claustrophobic. Imagining myself knowing that I may not have enough food in the house—that suddenly my next meal is utterly contingent on the capacities and goodwill of the state—I feel panicked.

If dozens of underfunded community organisations could prepare hundreds of meals at the drop of a hat, an equally well-prepared team could have been there to deliver these meals to the apartment residents by suppertime.

The last thing any tower block resident needed in that situation was for food to be dropped thoughtlessly on their doorstep at 2AM by someone carrying a gun.

That should not have happened to a single household in those blocks, especially since many may have had very good reasons to be fearful of police in the first place.

We don’t know how this pandemic will continue to unfold in the coming weeks and months. At least the burden of lockdown is somewhat more shared across metropolitan Melbourne, as it should be. But, should government authorities ever again face such an extraordinary situation, I hope that they will ask themselves this question: what would Lily do?

About the author:

Co-Chair, Sustain - Lecturer, William Angliss Institute

Dr Kelly Donati developed and lectures in Australia’s first Bachelor of Food Studies and Master of Food Systems and Gastronomy in the Faculty of Higher Education at William Angliss Institute. She has published widely in the areas of multispecies gastronomy, community gardens, farmers markets, the politics of Slow Food and the development of food studies pedagogy.