COVID-19 and the Crisis of the Commodified Food System

Dr Nick Rose, Executive Director, SustainHistory is being written right now. Are you authoring this chapter – or watching others do it for you?

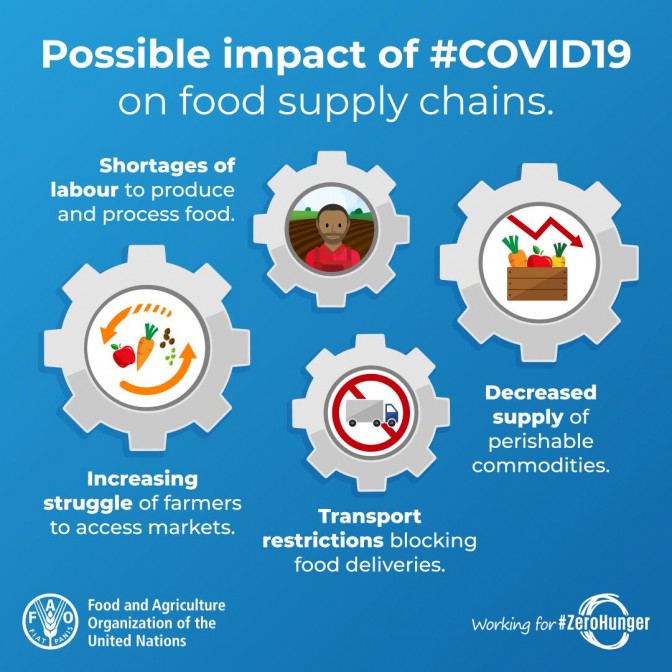

“The COVID-19 health crisis has brought on an economic crisis, and is rapidly exacerbating an ongoing food security and nutrition crisis. In a matter of weeks, COVID-19 has laid bare the underlying risks, fragilities, and inequities in global food systems, and pushed them close to breaking point.

Our food systems have been sitting on a knife-edge for decades: children have been one school meal away from hunger; countries – one export ban away from food shortages; farms – one travel ban away from critical labour shortages; and families in the world’s poorest regions have been one missed day-wage away from food insecurity, untenable living costs, and forced migration.

The lockdowns and disruptions triggered by COVID-19 have shown the fragility of people’s access to essential goods and services. In health systems and food systems, critical weaknesses, inequalities, and inequities have come to light. These systems, the public goods they deliver, and the people underpinning them, have been under-valued and under-protected. The systemic weaknesses exposed by the virus will be compounded by climate change in the years to come. In other words, COVID-19 is a wake-up call for food systems that must be heeded.

The crisis has, however, offered a glimpse of new and more resilient food systems, as communities have come together to plug gaps in food systems, and public authorities have taken extraordinary steps to secure the production and provisioning of food. But crises have also been used by powerful actors to accelerate unsustainable, business-as-usual approaches. We must learn from the lessons of the past and resist these attempts, while ensuring that the measures taken to curb the crisis are the starting point for a food system transformation that builds resilience at all levels.

This transformation could deliver huge benefits for human and planetary health, by slowing the habitat destruction that drives the spread of diseases; reducing vulnerability to future supply shocks and trade disruptions; reconnecting people with food production, and allaying the fears that lead to panic buying; making fresh, nutritious food accessible and affordable to all, thereby reducing the diet-related health conditions that make people susceptible to diseases; and providing fair wages and secure conditions to food and farmworkers, thereby reducing their vulnerability to economic shocks and their risks of contracting and spreading illnesses.” (emphasis added)

COVID-19 and the crisis in food systems: Symptoms, causes and potential solutions

Communique by IPES-Food, April 2020

These opening paragraphs from the Communique released this month by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) provide an excellent summary of what the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed about national food systems and the globalised, industrialised food system.

Our food systems, global and national, are fundamentally inequitable and unfair. While we have watched in fascinated horror as the daily toll of cases and fatalities from COVID-19 mounts, we have forgotten – if we ever gave it much thought - the silent, constant catastrophe of preventable early deaths caused by poverty, including lack of access to adequate nutrition, as well as safe drinking water and basic health care. According to the World Health Organisation, 6.2 million children and youth under 15 died from these causes in 2018. That’s nearly 17,000 every day, or around 12 deaths every minute. Every minute, every day. It cannot be said in strong enough terms: in a world where a tiny fraction of humanity enjoys lives of almost infinite riches, our politics and economy stand indicted as morally bankrupt, insofar as death and suffering on such a vast scale is effectively accepted within this paradigm as ‘normal’.

Yes, the international community of nations – the United Nations - has signed up to the Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 2 is ‘Zero Hunger’, with targets to end hunger and all forms of malnutrition. However, those goals and targets do not address the fundamental imbalances in power and maldistribution of wealth that produce so much poverty, suffering and hunger amidst so much abundance. As Eric Holt-Gimenez, Director of the campaigning organisation Food First, wrote back in 2012, “We Already Grow Enough Food for 10 Billion People…And Still Can’t End Hunger”. Why not? Because, as he argued, "hunger is caused by poverty and inequality, not scarcity".

Nor, I would add, is it caused by natural disasters or pandemics. The COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating this basic inequality in global and national food systems. It has been said that ‘we’re all in this together’ because the disease doesn’t respect boundaries of class or nations. That is true – up to a point. It’s also the case that those most impacted in terms both of exposure to COVID-19 and to the economic crisis that government public health policy responses have caused will be those who are most vulnerable. Low income and casual workers; farm and migrant workers; grocery store and delivery workers – all of whom do not have the option of working from home. And many of whom are not being provided with adequate protective equipment as they go about their essential work. As a result, increasing numbers of such workers are becoming infected with COVID-19 and many are dying. This is further proof, if it were needed, of a society and economy where the requirements of corporations for profit trump the rights of workers to a safe working environment.

Demand for the services provided by foodbanks has skyrocketed in the United States, as an extraordinary 22 million workers filing for unemployment claims in the past few weeks has seen queues of thousands of cars up to 10 kms long at many pop-up emergency food distribution points in various states. In the UK, the reports of a survey conducted for the Food Foundation over 7-9 April found that ‘the number of adults who are food insecure in Britain is estimated to have quadrupled under the COVID-19 lockdown’. The most heavily impacted are the disabled, the unemployed, and those from Black and ethnic minority groups. In Australia, where last year an estimated 20% of the population experienced food insecurity, emergency food providers are experiencing very high demand in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis even as supplies diminish through the collapse of the hospitality sector as a result of the enforced lockdown measures. Meanwhile in the US, the plunging of demand from restaurants and hotels has left farmers with no buyers for their produce; and as a consequence, millions of tonnes of milk, eggs and vegetables are being destroyed or ploughed back into the soil even as queues for foodbanks stretch ever longer.

The IPES-Food report also references the fragility of the industrial food system through supply chain disruptions, which may be caused by the closing down of processing facilities because of infected workers, or by a severe shortage of migrant workers due to border closures. Prior to the outbreak of the crisis, the entire model of factory farming, with its thousands and millions of animals confined in small spaces, was a known breeding ground for pathogens, most recently the swine flu and the avian flu. The COVID-19 pandemic is indeed a ‘wake up call for our food system’, in the words of IPES-Food. And this is without even discussing the other destructive impacts of the food system, such as its role in climate change, biodiversity loss and alarming rise in diseases linked to diet.

The case for change is urgent and overwhelming. It has been urgent and overwhelming for many years. What has shifted is that the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic crisis has brought the sheer wastefulness and inequality of the global and national food systems into the sharpest relief. In 2016, the Right to Food Coalition, including Sustain, stated that Australian governments – at all levels – were ‘failing their legal and moral obligation to guarantee the human right to adequate food for at least 1.2 million people who don’t have access to safe, affordable and nutritious food’. The Right to Food Coalition noted that Australia, despite being one of the richest countries in the world, was actually regressing in terms of its fulfilment of this basic and universal human right.

That regression is accelerating in the contemporary crisis – but out of crisis also comes disruption and opportunity. In their communique, IPES-Food noted that the past several weeks have also been notable for a ‘remarkable upsurge of solidarity and grassroots activism’ in many places around the world. The crisis has thus ‘offered a glimpse of what new and more resilient food systems might look like’. One of the most extraordinary and wonderful examples cited in the communique is the state of Kerala in India, which has funded and supported hundreds of community kitchens run by women’s networks to provide nutritious and free meals to the most vulnerable, delivered directly to their doorstep. In Melbourne, a collaboration of social enterprises led by STREAT has established the Moving Feast initiative, aiming to source and provide thousands of free meals to those in need through a network of kitchens, councils, social enterprises and emergency food relief agencies. On a local level, Sustain is working with partners at the Melbourne Food Hub on a Food Security and Food Justice Drive to mobilise the power of urban agriculture in helping to make good and fresh food available to those who need it most. We are supporting Community Gardens Australia and dozens of organisations and individuals who are calling on all governments across Australia to recognise community gardening and urban agriculture as an essential service, for the multiple benefits it provides to the Australian community – now more than ever.

History is being made as we speak. If you believe in the possibility of a better and fairer food system – and in a better and fairer world – now is the time to get involved in shaping it. We can and must do it together. Join us and let’s make it happen!